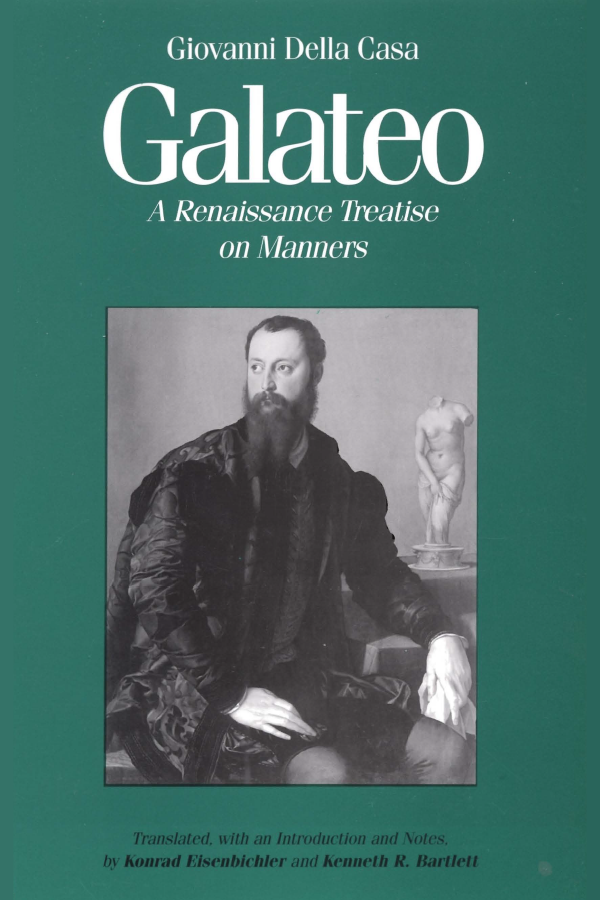

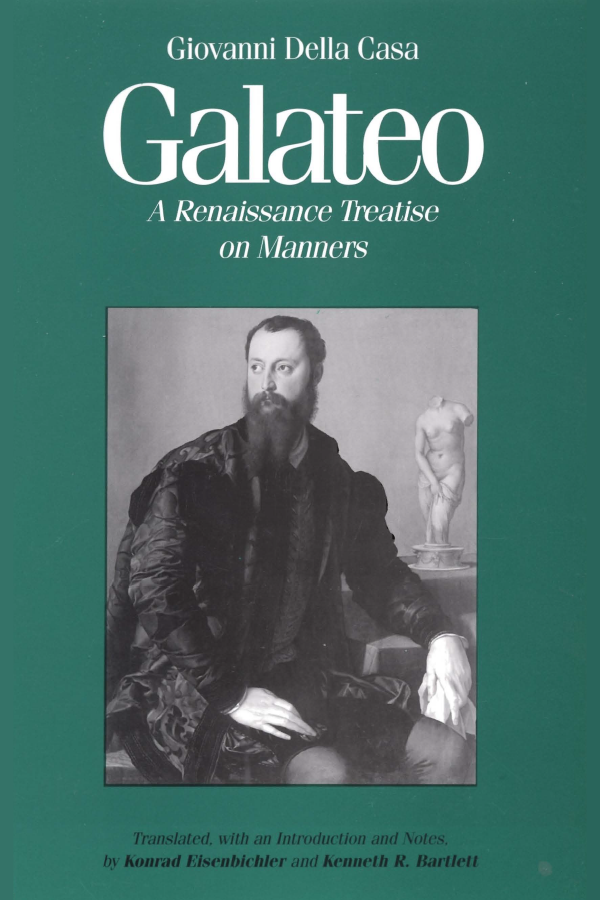

Galateo: A Renaissance Treatise on Manners, by Giovanni Della Casa

Edited and Translated by Konrad Eisenbichler and Kenneth R. Bartlett

Overview

Courtesy books have a special relationship to the age that produces them. By attempting to codify manners, styles, ideals and values of a society, they reveal the principles and presuppositions that shape and animate their world. Galateo does this brilliantly. It reflects the personal experience, wisdom, disappointments, and ambitions of its clerical but worldly-wise author, as well as the fundamental values of his age. And, given that his age was that of the transformation from the High Renaissance in Italy to the world of the Counter-Reformation, and that Della Casa was an important actor in the events of his time, the lessons are particularly valuable and worth considering.

Archbishop Giovanni Della Casa (1503-1556) was an influential Vatican diplomat, papal nuncio to Venice, and instrumental in the establishment of the Venetian Inquisition and in its 1549 Index of Prohibited Books. He was also an accomplished poet, an arbiter of taste, and the most influential writer on social practice of his time. His book, Galateo, has in fact provided the modern Italian term for good manners: “not to know the galateo” is to have no manners at all!

3rd Revised Edition.

Kenneth R. Bartlett is Professor of History and Renaissance Studies at Victoria College in the University of Toronto.

Konrad Eisenbichler is Professor of Italian and Renaissance Studies at Victoria College in the University of Toronto.

To View an Excerpt:

100 pp.

ISBN: 978-0-9697512-2-9 softcover

Published: 2009

Contents

Introduction

Galateo

Chapter 1. Preamble. The matter to be treated is presented; a comparison of good manners with other more remarkable virtues; the usefulness of this doctrine and the ease with which it may be put into practice

Chapter 2. What constitutes bad manners; what acts are displeasing to those with whom one deals. These are divided according to the senses which they offend

Chapter 3. We begin with those things which disturb the senses and, through them, the mind, and of some things which disturb our desires

Chapter 4. In order to make known how the small things which have been discussed ought not to be neglected, the author tells what Messer Galateo did to Count Ricciardo by order of the Bishop of Verona

Chapter 5. We return to dealing with the bad habits which displease the senses

Chapter 6. In order to proceed with a discussion of what men dislike, the author first explains what men desire in their dealings with others, and what is to be avoided because it implies a low opinion of that company

Chapter 7. How one should dress in order not to show disrespect to others

Chapter 8. On people who upset everybody; on conrrary and eccentric people. How hateful arrogance is, and how one should avoid anything which may be attributed to arrogance

Chapter 9. How always being contrary alienates other people; one should show affection for others and hold dear their love

Chapter 10. Of things which are contrary to human desires; the pleasure and amusements which people seek in conversation; but first, of sensitive and affected persons

Chapter 11. What topics should be avoided in conversation so as not to offend

Chapter 12. The habit of telling one's dreams in a conversation is especially to be condemned

Chapter 13. How much lies, boasting, and false modesty displease and should be avoided

Chapter 14. What ceremonies are, why they are called so, and how they should be observed

Chapter 15. Ceremonies are divided into three types. Those that are done for our own good are unbefitting to a well-mannered man

Chapter 16. One should never forego those ceremonies which are observed out of duty. The authority and strength of their usage. What to be wary of in observing them. To exceed in ceremonies is adulation unworthy of a gentleman. This is the third kind of ceremony, those observed out of vanity. How bothersome and unpleasant adulation is

Chapter 17. About other empty and superfluous ceremonies: they are an indication of little talent and an uncouth personality

Chapter 18. About slander, contradiction, giving advice, reprimanding and correcting other peoples' defects. Each of these things is bothersome

Chapter 19. Under no account should one mock someone else; what differentiates mocking from joking; one should generally avoid even the latter; when they are used, what care must be taken; two kinds of witticism; one must never use a biting wit

Chapter 20. Witty remarks are discussed in detail; they must be graceful and subtle; they are characteristic of sharp minds; they should not be used by those who do not have a natural disposition towards them; how anyone can determine whether or not he has any ability to be witty in a pleasant manner

Chapter 21. About long, continuous narrations. Rules are given on how to tell a story to the amusement and pleasure of the listeners

Chapter 22. In every kind of speech the words must be clear and appropriate to the subject; it is better for everyone to speak in his own rather than in another language; one should avoid vulgar words, as well as coarse words; everyone should accustom himself to modest and sweet speech, avoiding harsh and rough manners

Chapter 23. Other observations on speech. One should not speak before having carefully determined the subject matter of one's discourse. How one should regulate one's voice. Words must be well ordered. One should not use pompous, base or plebeian expressions. The enunciation should be suitably pleasant

Chapter 24. About talkative people; those who like to be the only ones to speak; those who interrupt others who are speaking; and the different kinds of faults that are committed in this. Why talkative persons are not liked; persons unduly taciturn are also disagreeable, and the reasons for this

Chapter 25. The author tells a story about a sculptor and apologizes for not practising what he preaches. He then seizes the opportunity to advise his listener to become accustomed to good manners in his youth. He explains the excellence of reason and its power against natural inclinations, and he sums up briefly what he has said up to now

Chapter 26. Wanting to explain what things are to be avoided because they are displeasing to the intellect, he first says that man desires beauty and proportion. He describes what beauty is and how it is found not only in the body but also in words and deeds

Chapter 27. Why things that are unpleasant to the senses and to human desires are also displeasing to the intellect, even though each has been discussed separately

Chapter 28. In all his actions a well-mannered man must seek grace and decorum. Vices are the worst of all base things, and therefore they are to be avoided. Many actions which must be carried out with proper manners are examined in detail, and clothes are specifically discussed

Chapter 29. Particular instances of bad table manners; and the opportunity is seized to say something against excessive drinking

Chapter 30. Many other foul and unsuitable manners to be avoided are mentioned, and with this the treatise is brought to an end

Praise

“This translation, in a contemporary English that avoids excessive colloquialisms, makes readily accessible to everyone interested in Renaissance culture a text that is not only a major book of etiquette but an illuminating study of the ideals of sixteenth century Italian Society. Through the text and its notes […] Eisenbichler and Bartlett anticipate the needs of readers for historical and mythological information. Eisenbichler and Bartlett have rendered an invaluable service to all students of the Italian Renaissance.”

— Douglas Radcliff-Umstead, Renaissance and Reformation/Renaissance et Reformé 26/3 (2002), pp. 241-242.

Reviews

CHOICE: Current Reviews for Academic Libraries, 24 (December 1986), p. 630.

Couldn't load pickup availability